Fire and Ice Entertainment officially unveiled its expanded creative ecosystem with a day of music, storytelling, and significant announcements. The launch brought together concerts, upcoming music releases, original films and series, and theatre productions that will be introduced throughout 2026.

The grand media launch at

Noctos Music Bar brought together artists, industry partners, press, and cultural stakeholders as Fire and Ice Entertainment introduced its five interconnected brands: Fire and Ice LIVE!,

Fire and Ice Music, Fire and Ice Studios,

Fire and Ice Media, and

Fire and Ice Consultancy.

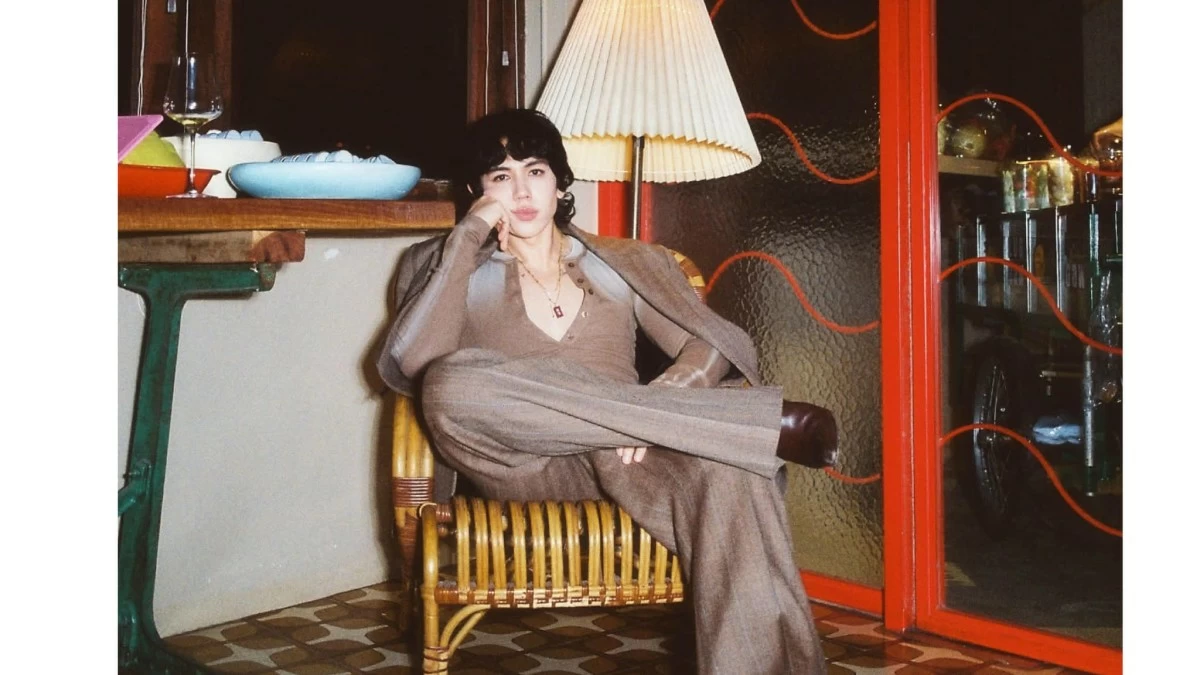

OPM icon Ice Seguerra,

Liza Diño, Chief Executive Officer of Fire and Ice Entertainment, and other Filipino artists pose during the Fire and Ice Entertainment trade show held in Quezon City.

These divisions together create an artist-led platform spanning live events, music, theatre, film, series development, and cultural consultancy—a significant evolution from project-based work to a fully integrated creative ecosystem.

Beyond a company launch, the event established Fire and Ice Entertainment as a lasting creative home for artists, prioritizing sustainability, authorship, and collaboration over one-off projects.

“Fire and Ice Entertainment was built on the belief that artists and ideas deserve long-term support, not just one-off projects,” said Liza Diño, Chief Executive Officer of Fire and Ice Entertainment. “By formally launching these five brands, we are putting structure behind a vision that allows creativity to thrive across live performance, music, screen, theatre, and cultural development while contributing meaningfully to the growth of the Philippine creative industry.”

Fire and Ice LIVE!: Expanding the live entertainment landscape

Fire and Ice LIVE! presented an extensive lineup of major concerts and live productions for the year, underscoring its commitment to high-quality, artist-focused live experiences.

Confirmed headline events include:

●

Being Ice: Live! at the New Frontier – Feb. 27, New Frontier Theater, headlined by Ice Seguerra

● Love, Sessionistas – April 18, Waterfront Cebu Hotel and Casino

● Sittiscape: The City of Bossa – May 17,

Newport Performing Arts Theater, featuring Sitti

●

Divine Divas: Divine Rules the World – May 31, Newport Performing Arts Theater, starring the Divine Divas.

Fire and Ice LIVE! also announced overseas touring plans, with “Being Ice” scheduled to visit Australia and Europe, signaling the company’s expanding international ambitions.

To further strengthen its presence in theatre, Fire and Ice LIVE! in partnership with Fire and Ice Studios announced upcoming stage productions:

● Still Alice (Sept. 27 – Oct. 5)

● ’Night, Mother (Nov. 26 – Dec. 5)

Fire and Ice Music: Building artist-centric careers

Fire and Ice Music officially unveiled its artist roster, underscoring the company’s commitment to music as a platform for creative expression and career growth. The initial lineup features Ice Seguerra, Princess Velasco, Divine Divas (Precious Paula Nicole, Viñas DeLuxe, Brigiding), and Louise.

The label also announced a slate of upcoming EP releases:

● Tamang Panahon – Ice Seguerra

● Always You – Louise

● Divine Rules The World – Divine Divas

● Still Here – Princess Velasco

These releases are part of a wider strategy focused on original music, narrative-driven projects, and increased artist participation in creative decision-making.

Fire and Ice Media: Original stories for screen and sound

Fire and Ice Media described its expanding pipeline of screen and audio projects, combining auteur-driven works by established and emerging filmmakers with original projects developed by the in-house creative team. This reinforces the company’s commitment to long-form storytelling in film, series, documentary, and audio.

Feature films:

● Karaoke News directed by John Paul Su

● Becoming Ice documentary by Tey Clamor

● Funeral Flowers - an original Fire and Ice Media project by Liza Diño and Ice Seguerra

● Island Girl - an original Fire and Ice Media project by Ice Seguerra

Series in development:

● Never The Bride - an original series created by Liza Diño

● Behind The Line - an original series created by Liza Diño

Key announcements include the return of Talk Sheets with Ice and Liza for its second podcast season.

Fire and Ice Consultancy: Creative Strategy and Cultural Development

Completing the ecosystem is Fire and Ice Consultancy, the company’s professional advisory arm focused on cultural, creative, and strategic consulting. Initial initiatives include consultancy support for

UNESCO Creative City applications and involvement in the development of QCinema Industry 2026, extending Fire and Ice Entertainment’s impact beyond production into policy and cultural planning.

Fire and Ice Entertainment: A multi-platform creative group

“At the heart of Fire and Ice is the artist. Everything we announced today—concerts, music releases, films, theatre productions—comes from a desire to create work that is honest, intentional, and deeply collaborative,” said Ice Seguerra, Fire and Ice Entertainment’s Chief Creative Officer. “This ecosystem allows artists to tell their stories across different platforms without losing their voice.”